There’s a bit of a puzzle about how applied ethics could be philosophically interesting. After all, the correct answer to an applied ethics question is presumably determined by the correct moral principles as applied to the particular empirical circumstances. The question of which moral principles are correct is a matter for the subdiscipline of normative ethics. Determining the empirical details (including probable consequences, etc.) is immensely important, but not a philosophical matter (and not something that philosophical training helps us to answer). So what is there for the applied ethicist to do?

It’s no good to just assume a moral theory, assume some empirical details, and then draw the obvious conclusion entailed by the combination. That’s too trivial—there’s no “value added” by work that just draws obvious inferences from stipulated premises.

One alternative is to pursue applied ethics without principles. Just look closely at the particular details of a case, draw attention to the features that seem most morally relevant, and form a holistic judgment about what “seems right”. I’m suspicious of this methodology because I think the invoked intuitions about cases are often shallow and biased, overly influenced by whatever factors are most psychologically salient or emotionally arresting, and so may fail to be systematically defensible in light of other judgments that are at least as intuitively compelling. So I think it’d be a mistake to eschew moral principles entirely.

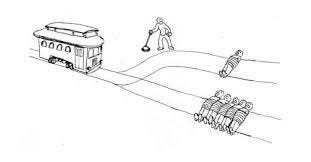

A better option may be to appeal to mid-level principles likely to be shared by a wide range of moral theories. Indeed, I think much of the best work in applied ethics can be understood along these lines. The mid-level principles may be supported by vivid thought experiments (e.g. Thomson’s violinist, or Singer’s pond), but these hypothetical scenarios are taken to be practically illuminating precisely because they support mid-level principles (supporting bodily autonomy, or duties of beneficence) that we can then apply generally, including to real-life cases.

The feasibility of this principled approach to applied ethics creates an opening for a valuable (non-trivial) form of theory-driven applied ethics. Indeed, I think Singer’s famous argument is a perfect example of this. For while Singer in no way assumes utilitarianism in his famous argument for duties of beneficence, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the originator of this argument was a utilitarian. Different moral theories shape our moral perspectives in ways that make different factors more or less salient to us. (Beneficence is much more central to utilitarianism, even if other theories ought to be on board with it too.)

So one fruitful way to do theory-driven applied ethics is to think about what important moral insights tend to be overlooked by conventional morality. That was basically my approach to pandemic ethics: to those who think along broadly utilitarian lines, it’s predictable that people are going to be way too reluctant to approve superficially “risky” actions (like variolation or challenge trials) even when inaction would be riskier. And when these interventions are entirely voluntary—and the alternative of exposure to greater status quo risks is not—you can construct powerful theory-neutral arguments in their favour. These arguments don’t need to assume utilitarianism. Still, it’s not a coincidence that a utilitarian would notice the problem and come up with such arguments.

Another form of theory-driven applied ethics is to just do normative ethics directed at confused applied ethicists. For example, it’s commonplace for people to object that medical resource allocation that seeks to maximize quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) is “objectionably discriminatory” against the elderly and disabled, as a matter of principle. But, as I argue in my paper, Against 'Saving Lives': Equal Concern and Differential Impact, this objection is deeply confused. There is nothing “objectionably discriminatory” about preferring to bestow 50 extra life-years to one person over a mere 5 life-years to another. The former is a vastly greater benefit, and if we are to count everyone equally, we should always prefer greater benefits over lesser ones. It’s in fact the opposing view, which treats all life-saving interventions as equal, which fails to give equal weight to the interests of those who have so much more at stake. (Compare flipping a coin to decide whether to give a drug to cure one person’s sore throat or another’s life-threatening sepsis. Such indiscriminate action fails to give due weight to the vastly greater interests of the latter person. They have so much more at stake than a sore throat!)

I think there’s a fair bit of scope for more of both kinds of theory-driven applied ethics to improve our collective understanding. People are often badly normatively confused in their thinking about practical problems. Sometimes we can make progress by clarifying a key normative concept (e.g. objectionable discrimination). Other times we might need to formulate mid-level principles that have cross-theory appeal, but are perhaps especially salient from our theoretical starting point. I think this is all worth doing, and I’d encourage more ethical theorists to do more of it.

Related to this, curious to know what you think of Philip Kitcher’s idea (in The Ethical Project and Moral Progress) that we should do away with the search for an all-encompassing theory of morality and instead focus on how moral progress was made in the past and try to mimic it. He argues this on the grounds that high level theories of ethics haven’t had much of an effect in practice on how people and countries act.