Much of conventional ethics is concerned with how we react to events that unambiguously impinge upon our lives. This may partly explain why we find it so much more obvious that we should save the child in Singer’s pond than that we should go out of our way to find other kids who need help, such as by donating to effective charities. Actually helping others (or doing good more generally) is thus not really a goal of much ordinary ethics, because the latter isn’t goal-directed at all.1 I think this is bad. This post will expand upon why we should prefer a more deliberate, goal-directed conception of our ethical lives (at least in part).2

The Demandingness Distraction

One nice (for us privileged folks) thing about reactive ethics is that it typically isn’t very demanding (for us). It can demand a lot of folks who stand to lose under status-quo conditions: if you need a kidney, you can’t just take a spare from me without my consent (even if refraining will kill you). But for those of us who are well-off under the status quo: we’re golden. If we mistakenly venture into the poor quarter of town, we may need to help out a homeless person or two. But if we’re more careful in where we go, and empower law enforcement to keep the riff-raff out of our regular haunts, we should be able to avoid even that.

OK, I clearly don’t think much of this purely selfish argument. But a more moderate version is available that highlights the unending demands of impartial consequentialism: whenever I wanted to do something for myself, I could always be doing more for others instead, and who could live like that? The only principled way to limit the demands of beneficence (you might think) is to refuse to acknowledge beneficent goals at all, and instead limit yourself to reacting virtuously to the stimuli that impinge upon your bubble.

I feel the force of not wanting to be subject to unending demands. But rejecting beneficent goals is a terrible response. A much better alternative, IMO, is to compartmentalize and just allow ethics to dictate a limited portion of one’s budget. In principle, this needn’t be any more demanding than the alternative. If you already guiltily hand out occasional alms to the homeless (or whatever), you could give that same amount, just more effectively. Better yet, you might find on reflection that a happy compromise with your core values would lead to giving a bit more than previously—but still not in a way that causes you any personal difficulty. (Many folks throughout history, much poorer than basically anyone likely to be reading this today, have tithed 10% without complaint.)

So: you can limit demandingness without rejecting goal-directedness. How much you allow ethics to shape your life, and whether you allow it to shape you in strategic or merely reactive ways, are separable questions—and worth explicitly separating.

Strategic Opportunities

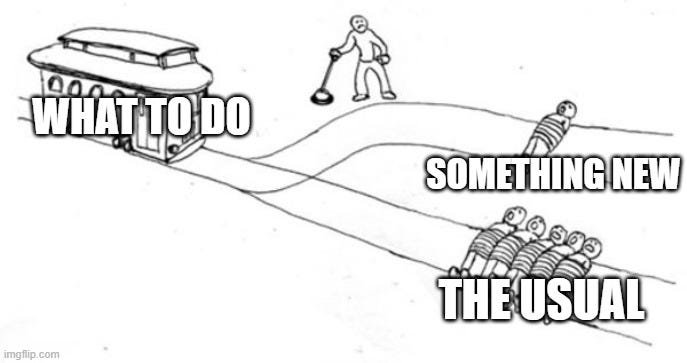

The positive case for goal-directedness is trivial: as a general rule, you’re more likely to do better if you at least try. While most of our lives are inevitably run on auto-pilot, it’s worth at least occasionally stepping back and explicitly reflecting on what we could do differently to better achieve our goals. And that’s especially true of moral goals.

Those of us living in wealthy countries are basically only exposed to “first world problems”. Many of these are indeed important and worth addressing, considered in their own right. But they’re mostly not nearly as important as the life-and-death challenges faced by many in developing countries. And even amongst first-world problems, the ones that tend to be most salient to us are hot-button “culture war” issues rather than duller but objectively more important issues like pandemic preparedness or the horrors of factory farming. Taking a calm moment to explicitly (i) survey the option space, and (ii) prioritize amongst competing moral issues, could easily lead to you doing orders of magnitude more good with your moral efforts than otherwise.

So I really want to encourage more people to try this. The next time you’re feeling morally motivated, try to harness that energy for a moment before letting loose. Ask yourself, of your default plan, is this the best thing in the world for me to be addressing right now? Not to be discouraging, but to open up your option space: maybe you could be doing something even better, at no greater personal cost. If so, make the switch!

My sense is that this kind of strategic prioritization is very alien to many worldviews, and constitutes the most distinctive (and controversial) contribution of Effective Altruist thought to practical ethics. To be opposed to EA as an idea, one must be opposed to the very notion of strategic prioritization, or goal-directed ethics. And some people evidently are very opposed to this. But I honestly can’t understand why (without ascribing bad faith). So I’d certainly welcome any attempts to explain how a decent person could reasonably be hostile to the very idea of seriously trying to do good, in a scope-sensitive, goal-directed way (preferring more good to less, all else equal).

Room for Pluralism

One thing I want to stress here is that nothing in the idea of goal-directed beneficence forces one to accept full-blown utilitarianism. You can supplement it with deontic constraints, partiality, etc. Be a Rossian pluralist, or a Cowenian “two thirds utilitarian”; let reactive ethics govern 90% of your life, but be strategically goal-directed for at least 10%. We all need to make practical compromises, I can respect that.

What I don’t understand is people who implicitly treat an argument against full-blown utilitarianism as a reason to reject goal-directed ethics in its entirety. These are very different things! Yet goal-directedness seems so rare in non-consequentialist thought that Effective Altruism is routinely conflated with “applied utilitarianism”. Why is this? Why not be a thoroughgoing pluralist, who incorporates goal-directed beneficence as a non-trivial part of their overall moral view? What reason is there to prefer a purely reactive ethics? Shouldn’t we regard the latter as utterly disreputable? (This isn’t rhetorical; I’d love to hear people’s answers.)

This may also help to explain the mystery of why beneficentrism is so rare amongst non-utilitarians.

This is all to expand upon the ‘permissibility is not enough’ section of my previous post on permissibility and moral importance: (Im)permissibility is overrated.

I know this is not the main point here, but I would really question the idea that people tithed 10% "without complaint". Tithes were often more like taxes than voluntary donations, and there were revolts against them, e.g.: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539720

I'm wondering how much overlap there is between apparent examples of reactive ethics and apparent examples of "expanding circle" moral weighting of others based upon metaphorical proximity to oneself. When people put a lot of effort into domestic political causes, it usually doesn't strike me as particularly reactive, but more like proactive altruism toward their respective political tribe first, their own nation second (possibly also including a few other select "similar" nations), and the faraway rest of the world mostly out of the calculation.