One of my more radical meta-philosophical views is that moral philosophers, collectively speaking, don’t have any clear idea of what they’re talking about when they talk about ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. There are too many candidate concepts available, and no obvious reason to expect different theorists to have the same one in mind. So we should expect that moral philosophy involves a lot of theorists talking past each other in very unproductive ways. (That’s not to say that we all actually agree; just that we haven’t yet gotten clear enough to properly understand where we disagree.)

Old news

As a first step towards validating this radical view, I previously argued that there is no substantive difference between “maximizing” and “scalar” consequentialism: they are purely verbal variants expressing one and same underlying view, and the positive claims of this “core” consequentialist view are perfectly compatible with the claims of satisficers, too. So the traditional assumption that maximizing, satisficing, and scalar consequentialisms were “rival” views one had to pick between really couldn’t have been more wrong.

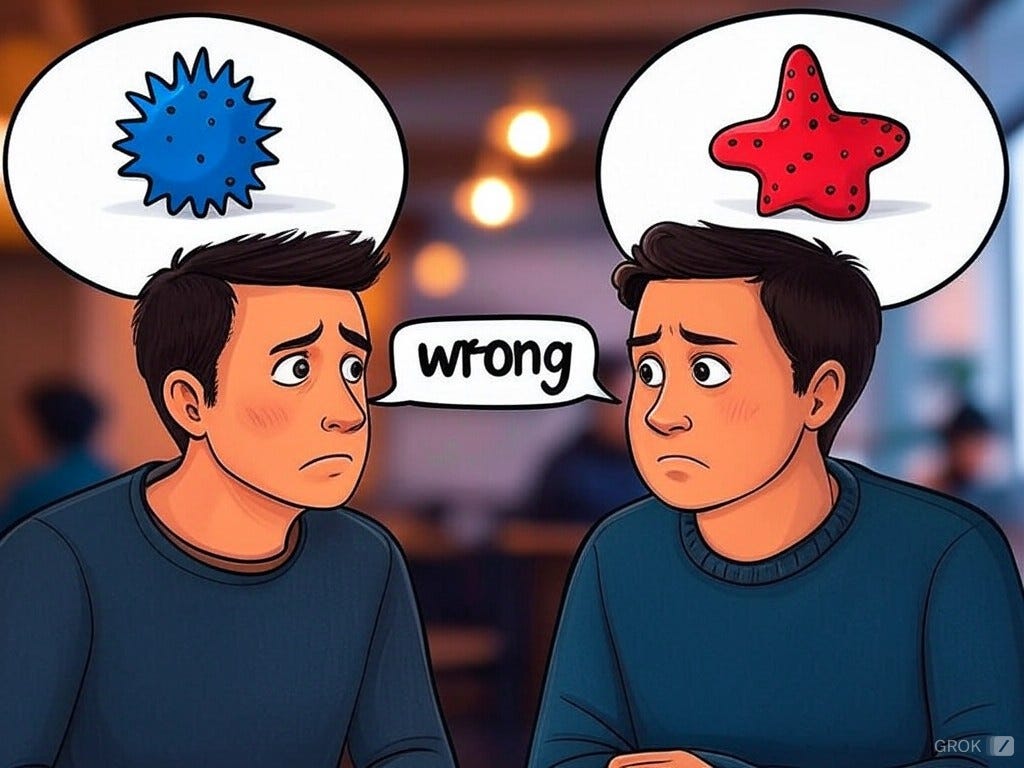

Philosophers were misled by the surface grammar—that each view seemed to say different things about what’s “right”—and didn’t stop to ask whether the same concept of rightness was being discussed each time. My past work demonstrates that the three theories are (best understood as) addressing different deontic concepts despite their shared use of the term ‘right’.

I now want to suggest that something similar could be going on in the debate between those who view Transplant-style “counterexamples” to consequentialism as decisive vs. those who (like me) think they are utterly insignificant.

Ideal vs Non-Ideal Decision Theory

Consequentialists have long distinguished their objective “criterion of rightness” from the “decision procedure” that they advise following. R. M. Hare distinguished “critical” and “intuitive” levels of moral thinking—the former playing more of a role in systematic theorizing, and the latter (again) being better suited to guiding everyday moral deliberation.

The two “levels” of moral thinking can obviously come apart. Whatever the correct moral goals turn out to be, there’s no empirical guarantee that naive instrumentalist pursuit will be the most reliable means of securing them. So we should fully expect that the best practical norms to inculcate and follow (in line with non-ideal decision theory) are not transparent to the correct ultimate ends. (This is even true of deontology.)

If moral education is successful, we internalize good practical norms, which we then find it intuitively objectionable to violate. Those are good, well-justified dispositions for us to have. (They’re not merely “useful” dispositions, as the orthodox consequentialist framing might suggest. They are, on my view, genuinely fitting/warranted dispositions, constitutive of instrumental rationality for non-ideal agents like ourselves. There’s a very real sense in which these verdicts reflect how we ought, practically, to seek to maximize the good.)

There are different ways to incorporate these insights into our ethical theorizing. The orthodox framing assumes that “rightness” is the “ideal theory” thing our theorizing is about (that is, something like objective desirability), and our justified resistance to killing people for the greater good in weird Transplant-style scenarios leads people to falsely conclude that the killing is actually “wrong” in the ideal-theoretic sense of being objectively undesirable.

But it’s worth highlighting an alternative candidate frame: “rightness” could instead be the “non-ideal theory” thing that justifiably guides our actions, in which case consequentialism agrees that Transplant-style killing is “wrong”, but this verdict has no implications for fundamental moral questions concerning objective desirability and associated objective reasons.

Words Don’t Matter, so nothing really hangs on which way of talking we adopt here—we should talk in whichever way best avoids misunderstandings (which may vary across different audiences). The important thing is just to understand that intuitive resistance to killing for the greater good (and other “ends-justifies-the-means” reasoning) is sufficiently explained by one’s grasp of the fact that Naïve Instrumentalism is the wrong decision theory (or account of instrumental rationality) for non-ideal agents. This result gives you zero reason to reject utilitarianism’s answer to the telic question (of what’s objectively desirable).

No answer to the telic question forces one to accept naive instrumentalism as a decision theory. Utilitarianism (as a fundamental moral theory) answers the telic question, not the decision-theoretic one. To get practical action-guidance, it needs supplementation with an account of instrumental rationality, i.e. a decision theory. Previous philosophers have tended to simply assume naive instrumentalism; but this is only plausible in ideal theory. Obviously non-ideal decision theory will look different. So, utilitarianism + non-ideal decision theory will not yield the counterintuitive verdicts that people tend to associate with utilitarianism. For example, it will (most plausibly) not imply that the agent in Transplant should kill an innocent person for their organs.

So, philosophers who take Transplant-style cases to refute utilitarianism have mistakenly conflated:

rightness in the ideal-theory sense of what’s objectively desirable in the described situation (rightideal); and

rightness in the non-ideal theory sense of what it would be rational or wise for a fallible human being to do when they judge themselves to be in the described situation (rightnon-ideal).

Utilitarianism implies that it is rightideal to kill for the greater good, but not rightnon-ideal. When we intuit that killing for the greater good is “wrong”, are we thinking about wrongness in an ideal or non-ideal sense? It’s far from clear.

I think it is most plausibly the non-ideal sense we have in mind, since that’s the one that’s operative in ordinary moral life and moral education (by means of which we acquired the concept in the first place). Philosophical training enculturates us into doing ideal theory instead. But the end result is that we’re theorizing about a different concept than the one that we started with, and that “commonsense intuitions about cases” tend to be about. (To be clear: I endorse this change of subject—there are excellent reasons to do ideal theory—but that’s a discussion for another day.)

The upshot is that those ordinary intuitions are no longer probative in ethical theory, because they don’t even address the same question that the utilitarian ethicist is trying to answer. Anyone who thinks utilitarianism is straightforwardly refuted by Transplant-style cases literally does not understand what they are talking about.

Reviving the Objections (if you can)

Of course, using different concepts doesn’t mean that a view is immune to intuitive objections or counterexamples. We just need to be sure that the meanings match up. To counterexample utilitarianism’s ideal-theory verdicts, for example, you need to imagine a scenario in which ideal theory applies; say, involving omniscient angels rather than fallible humans.

Would angels refuse to harvest organs from one innocent angel to save five? (Bear in mind that other angels are so altruistic that they wouldn’t be deterred from visiting hospitals even if knowledge of the event became prominent news. And the five in need of organs are just as psychologically salient to them as the one who is a candidate for harvesting. So they may find our question tendentious, and suggest we instead ask: “Would an angel allow five other angels to die when they could easily save them by killing and harvesting organs from just one other angel, no more or less deserving of survival than any one of the five?”)

It seems odd to think that one could be confident of the answer to this question in advance of figuring out what the correct moral theory is. You’re no angel—what do you know about angel ethics? We’d surely have to inquire carefully in order to have any hope of figuring out the answer. Ultimately, I think the arguments for utilitarianism provide extremely strong grounds for thinking that angels would act in the way that yields the best results (which, yes, could involve killing one to save five).

It’s very hard to see why we should give any weight to mere gut intuitions to the contrary, when (i) it’s clearly desirable that the act be done which produces the best outcome; (ii) robust deontological claims to the contrary end up tied in knots; and (iii) we can explain away the intuitive resistance as more plausibly addressing non-ideal theory.

Conclusion

People sometimes find it annoying when I argue that everyone else is confused. But people very often are confused—that’s why we need philosophy!1 And I think I’ve made a pretty strong case here for an important ambiguity, running throughout ethical theory, that has been systematically overlooked. It’s very common for people to hastily dismiss consequentialism on the grounds of transplant-style “counterexamples”. If I’m right about the deontic ambiguity noted in this post, these people are being too hasty. Their putative “counterexamples” are no such thing.

The core problem (that I wish to be more widely understood) is that deontic verdicts result from combining answers to the telic and decision-theoretic questions. The common caricature of utilitarianism combines utilitarianism proper (as an answer to the telic question) with naive instrumentalism (as a decision theory). If you reject the deontic verdicts associated with Caricatured Utilitarianism, that doesn’t yet settle whether the fault lies with utilitarianism or with naive instrumentalism. We already know there are very obvious reasons to reject the latter (as a non-ideal theory). So the rejection of Caricatured Utilitarianism’s deontic verdicts doesn’t yet establish that there is any reason at all to reject utilitarianism proper.

Let me know if you disagree—these ideas will inform Part III of Beyond Right and Wrong.

“The cause of—and solution to—all of life’s problems,” as Homer Simpson once put it. (Though he may have been speaking of beer, rather than philosophy.)

This all sounds exactly right to me!

(Though regarding your offhand mention of satisficing - I think the concept of satisficing has often been crudely adopted by philosophers as the idea that there is some threshold such that everything above that threshold is “good enough” and everything below that threshold isn’t, while I think Herb Simon intended it as a decision procedure where one evaluates options one by one in the order they come to mind and then does the first one that passes the threshold. It could well be that this decision procedure with a particular threshold actually optimizes the tradeoff of time considering vs goodness of act done.)

I am now more confused.