In the wake of the current dysfunction in Congress, the NY Times editorial board asks, ‘Why Is the Public’s Business at the Mercy of a Few Extremists?’ It’s a strange situation: why are our politicians so much more extreme than the median voter? People like to talk about counter-majoritarian aspects of the US constitutional system: Jamelle Bouie cites an interviewer who mentions “the Electoral College, the nature of the Senate, the gerrymandering process…”. And those all seem like worthy targets for democratic reform. But if I had to pick just one problem to prioritize, I think it would have to be party primaries.

The core problem seems to be that, for many politicians (esp. all of those in “safe seats”), their greatest threat to re-election is not the general election but their party primary. As a result, they are not responsive to the median voter in the general electorate, but rather the median voter within their party’s base. An extremist minority may yet constitute “a majority of the majority”.1 In this way, the party primary system risks empowering clowns even when the median voter (of the general electorate) is broadly reasonable.

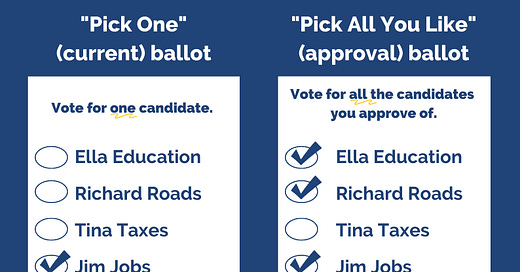

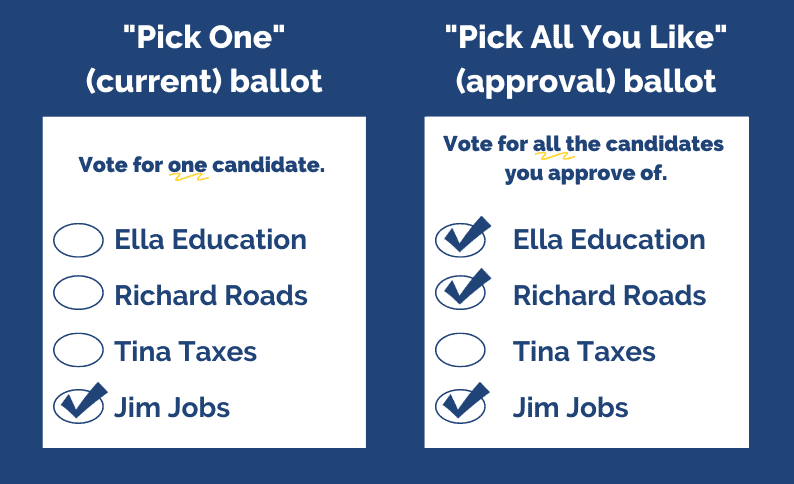

Party primaries are needed in order to avoid a “spoiler” splitting the vote between closely-aligned candidates (the same reason you don’t want a third-party challenger from your flank). But the problem of vote-splitting “spoilers” only arises in electoral systems where voters are only allowed to vote for one candidate amongst all those running. Change that system, and we no longer need party primaries.

Voting for multiple candidates

There are two main alternatives to single-candidate voting:

Approval voting simply asks voters to vote for every candidate they consider acceptable. Whoever is acceptable to the broadest swathe of the electorate will then end up winning.

Ranked choice voting (also known as instant runoff voting, or single transferable vote) asks voters to rank as many candidates as they like. If their top-choice candidate would lose, their vote instead gets transferred to their second choice, and so on, until (again) we settle on a winner who is broadly acceptable to most voters.

Ranked choice seems nice in that it’s responsive to finer-grained preferences: if a majority really like Awesome Abe, but a slightly larger majority find Dull Dwayne acceptable, RCV will award the election to Abe whereas approval voting would land us with Dwayne. But the greater simplicity of approval voting might nonetheless make it a better option in the real world. (The Center for Election Science has more on the comparison, here.)

Conclusion

While there are lots of electoral reforms I would favour (Brad Templeton explores a number of interesting possibilities here and here), my current top priority suggestion is to abolish the primary system by replacing single-candidate voting with approval voting for all general elections. Abolish party primaries, and you free the Republican party from the insanity of its MAGA base. Politicians in congress would be incentivized to work across the aisle to appeal to the widest possible range of voters rather than just their party base. In 2016, neither Trump nor Clinton would have been elected president, but some other—more broadly acceptable—candidate. Approval voting is a simple, non-partisan reform with the promise to immensely improve democratic outcomes.

But if you think I’m overlooking an even better alternative, do let me know!

Or, at least, a majority of the party that is, given other counter-majoritarian aspects of the system, able to win half the time even without a majority of overall voters supporting them.

Open primaries would seem like the more feasible alternative to those you have suggested. Additionally, the process is underway with twenty-four states having degrees of openness in the presidential primaries. Allow that process to expand to the legislative branch. The objections of dilution and clown stacking by the opposition haven't materialized.

There is a better alternative that's not merely theoretical, but widespread: a parliament, in which somewhat narrow voter preferences (collections of many correlated policy interests) are each able to gain representation, and then these narrower groups are rather freely able to negotiate larger coalitions.