With three books down—Parfit’s Ethics, An Introduction to Utilitarianism, and Questioning Beneficence1—I’m finally writing a monograph that sets out my own approach to ethical theory. With apologies to Nietzsche, I couldn’t resist the title: Beyond Right and Wrong.

I’m super-excited about the project (and its potential to reshape how we think about ethical theory), and am finding it a blast to write so far. One useful bit of advice I received about writing an academic monograph is to get feedback early and often. So I’m sharing my current outline here, in the hopes that some colleagues reading this may be interested enough to (i) want me to come give a talk to their department,2 and/or (ii) offer feedback on an early draft at some point.3

(Long-time readers may recognize several of the themes mentioned below from past Good Thoughts posts.)

Introduction to Beyond Right and Wrong

Much of ethical theory is framed around the project of completing the formula: “An act is right if and only if ...” Too much, I say. A central aim of this book is to encourage a shift in focus. In some ways, this is a modest task: I do not claim that one cannot (or mustn’t) inquire into the precise location of deontic boundaries—i.e., between the impermissible, the permissible, and the supererogatory. It’s a fine project, as far as it goes. I just don’t think it goes very far.

I think we can do better by thinking differently about the project of moral philosophy, the central questions of the field, and what the different answers signify. There’s something very ambitious about this claim: if I’m right, major changes are called for in how we do (and think about) ethical theory. But sweeping meta-philosophical claims can be difficult to assess in the abstract. So I also aim to demonstrate the philosophical benefits of my preferred approach to ethical theory.

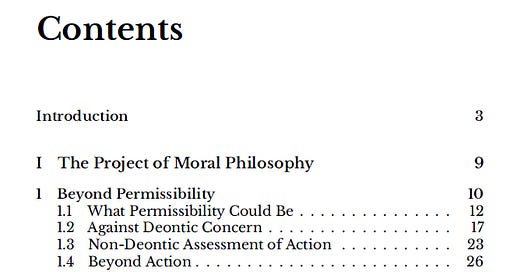

Part I: The Project of Moral Philosophy, makes the case for this reconceptualization. Chapter 1, Beyond Permissibility, argues against the common presupposition that moral agents should have a distinctive concern to avoid acting impermissibly. It further highlights two classes of normative assessment that risk being neglected when philosophers focus overly much on permissibility and its boundaries: (i) non-deontic assessments of actions, including prioritization within the permissible, and (ii) assessments of things other than actions—such as fitting attitudes.

Chapter 2, Telic vs Deontic Ethics, argues that ethical theory should most centrally address the telic question of what is worth caring about, rather than the deontic question of what is permissible. I argue that the telic question is both more theory-neutral and more transparently normatively significant. Both features make it an objectively better question around which to center normative inquiry.

Chapter 3, A New Methodology, then sets out a vision of how to do first-order ethical theory, in accordance with the meta-theoretical lessons of the previous chapters. I suggest that we ask two questions: (i) what matters? and (ii) what follows from the facts about what matters? I argue that this telic method is substantively illuminating, helping us to more easily appreciate why some influential putative objections are not really objections at all.

Part II: What Matters, takes up the first question. Chapter 4, Beneficentrism, defends the view that the general welfare matters immensely and warrants being among our central concerns. Whatever doubts one has about the other claims of utilitarianism, all should agree with this much. Deontologists should, following W.D. Ross, grant that there are extremely weighty reasons of impartial beneficence. Virtue ethicists should appreciate that benevolence is among the most important of virtues. Non-utilitarian consequentialists may allow agents to care especially about their nearest and dearest, in “agent-relative” fashion; but even so, the agent-neutral value of others cannot reasonably be denied.

Chapter 5, Puzzles for Everyone, explores the challenge of how to most coherently extend ordinary beneficence in light of the paradoxes of population ethics and decision theory. These paradoxes are often mistakenly believed to uniquely afflict consequentialists. I clarify that they are puzzles for everyone who recognizes the importance of beneficence—which is to say, everyone decent. They admit of no easy (or costless) solutions, contrary to common belief. But I propose what I take to be the best available. Along the way, I explain why I find anti-aggregative approaches to ethics inadequate.

Chapter 6, Anti-Moralism, sets out three reasons for doubting that deontic constraints warrant non-instrumental concern. The first generalizes from a broader skepticism about “sacred” values and sins. The second draws on the idea that we all have decisive ex ante reason to pre-commit to endorsing consequentialist verdicts, before we discover our particular station in life. Third, I present a new paradox of deontology which shows that bystanders cannot reasonably wish deontic constraints to be respected.

Part III: What Follows, explores the implications of what we should care about for other normative questions—including what we should do. Chapter 7, Ideal and Non-ideal Decision Procedures, refutes the naive account of instrumental rationality as attempting expected value calculations and then blindly acting upon whatever verdicts result. Once we reject naive instrumentalism, the connection between consequentialist concern and rational action becomes more complicated than generally appreciated. The chapter wraps up by comparing two ways one could go from here: (i) Two-level consequentialism, which adopts an act-consequentialist criterion of rightness but denies it any direct advisory role for non-ideal agents, and (ii) Deontic fictionalism, which adopts a rule-consequentialist criterion of rightness but denies it fundamental normative significance.

Chapter 8, Bleeding Heart Consequentialism, expands upon my preferred form of consequentialist theory. I show how attention to fitting attitudes and apt motivations allows consequentialists to accommodate many more commonsense intuitions than is generally appreciated—from the separateness of persons to a moderate form of the killing / letting die distinction.

Part IV: Reflective Equilibrium, surveys the normative landscape from our new and improved vantage point. Chapter 9, Weighing the Costs and Benefits of Non-Consequentialism, argues that commonsense intuitions offer little reason to prefer a deontological theory over the deontic fictionalism of chapter 7. Meanwhile, significant practical costs to deontology can be adduced, to supplement the grave theoretical costs identified in chapter 6.

Chapter 10, Principled Instrumentalism, argues that the consequentialist view that emerges in Part III is plausibly the overall best and most intuitive theory on offer. Too often, judgments about which moral theories are or are not “counterintuitive” rest heavily—or even exclusively—on intuitions about deontic verdicts. If, as I’ve argued throughout the book, deontic verdicts are less central to ethics than telic ones, it stands to reason that intuitions about deontic verdicts should play less of a role in reflective equilibrium than intuitions about telic verdicts. When we focus more on the latter, consequentialism becomes almost irresistible. And the implications most often identified as “objectionable” are revealed to be almost costless.

Postscript: online workshop?

I really want the book to be as good (and as influential within the discipline) as possible. So it could be helpful to run some kind of low-key online workshop4—where participants commit to reading at least one chapter, and then we collectively chat for a bit about possible ways to improve the manuscript—perhaps in late Fall or early Spring Summer 2025.

Academic philosophers (including students): if you’d be interested in participating, or otherwise offering feedback on an early draft at some point, shoot me an email to let me know!

Alternatively, if you already have suggestions for ideas or objections I should engage with, just based on the sparse overview above (and perhaps your background knowledge of my views and writing), feel free to comment below.

The last two are co-authored.

E.g., I have a fun talk, ‘Permissibility is Overrated’, which effectively summarizes the central ideas from Part I of the book.

See postscript.

Thanks to Colin for the idea!

With the twin caveats that I am not an academic philosopher and of course I don't know how this will intersect with your own vision of what you want this book to do, my attention was caught by your initial promotion of telic arguments at the beginning, and your claim at the end that "If, as I’ve argued throughout the book, deontic verdicts are less central to ethics than telic ones, it stands to reason that intuitions about deontic verdicts should play less of a role in reflective equilibrium than intuitions about telic verdicts. When we focus more on the latter, consequentialism becomes almost irresistible."

Because your promotion of a telic view of ethics is a new deeper standard, it seems to me that there is a risk that it could merge somewhat with your own more specific ethics in unnecessary ways. There is a risk that your "telic view" might have been phrased in such a way as to sneak a link to consequentialism in by the back door.

I can easily imagine people who agree that ethics should focus on the question "What matters?" but who would not find as a result that consequentialism becomes irresistible. The first and most obvious example that comes to mind is that of Christian-adjacent theism. Consider this rough paraphrase of Mark 12:30-31. "Firstly, love the Lord your God with all your heart and all your mind and all your strength. Secondly, love your neighbour as yourself." Many Christians would take this as an articulation from Jesus about the question "What matters?" The answer is that God matters firstly, and that other human beings matter secondly.

For the most part, Christians who say this do not mean that God "matters" in a consequentialist fashion. It is not that we should care about God in order that we may pay more attention to the effect that our actions will have upon the state of God! It is simply that God is worth caring about, regardless of whether we can actually have any effect on God.

If you think of "X matters" as meaning "we should care about the consequences of our actions in so far as they affect X," then a telic view would indeed lead to consequentialism! But this is not the only kind of "mattering" that, uh, matters to people.

I like the idea of your telic view very much. I think it contains insights that are worthwhile, regardless of whether they lead to consequentialism. I will leave it to you to decide whether the potential objection that I have raised has any bearing on what you are actually trying to do, here. Best wishes for your book!

I'd suggest trying very hard to get feedback from those who disagree. Those people are not normally reading your blog.