In Moral Misdirection, I argued that honest communication aims to increase the importance-weighted accuracy of your audience’s beliefs. Discourse that predictably does the opposite on a morally important matter—even if the explicit assertions are technically true—constitutes moral misdirection. Emphasizing minor, outweighed costs of good things (e.g. vaccines) is a classic form that this can take. In this post, I want to explore another case study: exaggerating the harms of trying to do good.

What’s Important

Here’s something that strikes me as very important, true, and neglected:

Target-Sensitive Potential for Good (TSPG): We have the potential to do a lot of good in the face of severe global problems (including global poverty, factory-farmed animal welfare, and protecting against catastrophic risks). Doing so would be extremely worthwhile. In all these areas, it is worth making deliberate, informed efforts to try to do more good rather than less with our resources: Better targeting our efforts may make even more of a difference than the basic decision to help at all.

This belief, together with a practical commitment to acting upon it, is basically the defining characteristic of effective altruists. So, applying my previous guidance on how to criticize good things responsibly, responsible critics of EA should first consider whether they agree that TSPG is true and important, and explain their verdict.

As I explain in my previous post (see #25) the stakes here are extremely high: whether or not people engage in acts of effective altruism is literally a matter of life or death for the potential beneficiaries of our moral efforts. A total lack of concern about these effects is not morally decent. Public-facing rhetoric that predictably creates the false impression that TSPG is false, or that acts of effective altruism are not worth doing, is more plainly and obviously harmful than any other speech I can realistically imagine philosophers engaging in.1 It constitutes literally lethal moral misdirection.

Responsible Criticism

To draw attention to these stakes is not to claim that people “aren’t allowed to criticize EA.” As I previously wrote:

I think it’s almost always possible to find a responsible way to express your beliefs. And it’s usually worth doing so: even Good Things can be further improved, after all. (Or you might learn that your beliefs are false, and update accordingly.)

But it requires care. And the mud-slinging vitriol of EA’s public critics is careless in the extreme, elevating lazy hostile rhetoric over lucid ethical analysis.

There’s no reason that criticism of EA must take this vicious form. You could instead highlight up-front your agreement with TSPG (or whatever other important neglected truths you agree we do well to bring more attention to), before going on to calmly explain your disagreements.

The hostile, dismissive tone of many critics seems to communicate something more like “EAs are stupid and wrong about everything.” (Even if this effect is not deliberate, it’s entirely predictable that vitriolic articles will have this effect on first-world readers who have every incentive to find an excuse to dismiss EA’s message. I’ve certainly seen many people on social media pick up—and repeat—exactly this sort of indiscriminate dismissal.) If TSPG is true, then EAs are right about the most important thing, and it’s both harmful and intellectually dishonest to imply otherwise.

Of course, if you truly think that TSPG is false, then by all means explicitly argue for that. (Similarly, regarding my initial examples of moral misdirection: if public health authorities ever truly believed that some vaccines were more dangerous than COVID itself, they should say so and explain why. And if immigrants truly caused more harm than benefit to their host societies, that too would be important to learn.) It’s vital to get at the truth about important questions, and that requires open debate. I’m 100% in favor of that.

But if you agree that TSPG is true and important, then you really should take care not to implicitly communicate its negation when pursuing less-important disagreements.

The critics might not realize that they’re engaged in moral misdirection,2 any more than Don the xenophobe does.3 I expect the critics don’t explicitly think about the moral costs of their anti-philanthropic advocacy: that less EA influence means more kids dying of malaria (or suffering lead exposure), less effective efforts to mitigate the evils of factory farming, and less forethought and precautionary measures regarding potential global catastrophic risks. But if you’re going to publicly advocate for less altruism and/or less effective altruism in the world, you need to face up to the reality of what you’re doing!4

Wenar’s Counterpart on “Deaths from Vaccines”

I previously discussed how academic audiences may be especially susceptible to moral misdirection based upon misleading appeals to complexity. “Things are more complex than they seem,” is a message that appeals to us, and is often true!

But true claims can still (very predictably) mislead. So when writing for a general audience on a high-stakes issue, in a very prominent venue, public intellectuals have an obligation not to reduce the importance-weighted accuracy of their audience’s beliefs.

Leif Wenar egregiously violated this obligation with his WIRED article, ‘The Deaths of Effective Altruism’. And a hefty chunk of our profession publicly cheered him on.

I can’t imagine that an implicitly anti-vax screed about “Deaths from Vaccines” would have elicited the same sort of gushing praise from my fellow academics. But it’s structurally very similar, as I’ll now explain.

Wenar begins by suggesting, “When you meet [an effective altruist], ask them how many people they’ve killed.” He highlights various potential harms from aid (many of which are not empirically well-supported, and don’t plausibly apply to GiveWell’s top charities in particular, while the few that clearly do apply seem rather negligible compared to the benefits), while explicitly disavowing full-blown aid skepticism: rather, he compares aid to a doctor who offers useful medicine that has some harmful side-effects.5

His anti-vax counterpart writes that he “absolutely does not mean that vaccines don’t work… Yet what no one in public health should say is that all they’re doing is improving health.” Anti-vax Wenar goes on to describe “haranguing” a pro-vaccine visiting speaker for giving a conceptual talk explaining how many small health benefits (from vaccinating against non-lethal diseases) can add up to a benefit equivalent to “saving a life”. Why does this warrant haranguing? Because vaccines are so much “more complex than ‘jabs save lives’!”

Wenar laments that the speaker didn’t see the value in this point—their eyes glazed over with the “pro-vax glaze”. He interprets this as the speaker having a hero complex, and fearing “He’s trying to stop me.” As I explain on the EA Forum, Wenar’s “hero complex” seems an entirely gratuitous projection. But it would seem very reasonable for the pro-vax speaker to worry that this haranguing lunatic was trying to stop or undermine net-beneficial interventions. I worry that, too!

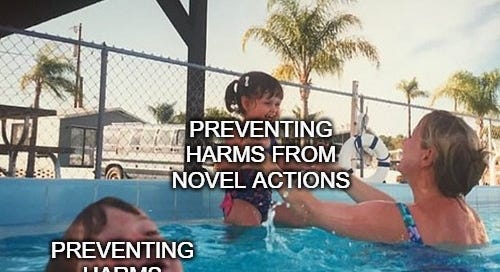

People are very prone to status-quo bias, and averse to salient harms. If you go out of your way to make harms from action extra-salient, while ignoring (far greater) harms from inaction, this will very predictably lead to worse decisions. We saw this time and again throughout the pandemic, and now Wenar is encouraging a similarly biased approach to thinking about aid. Note that his “dearest test” does not involve vividly imagining your dearest ones suffering harm as a result of your inaction; only action.6 Wenar is here promoting a general approach to practical reasoning that is systematically biased (and predictably harmful as a result): a plain force for ill in the world.7

Wenar scathingly criticized GiveWell—the most reliable and sophisticated charity evaluators around—for not sufficiently highlighting the rare downsides of their top charities on their front page.8 This is insane: like complaining that vaccine syringes don’t come with skull-and-crossbones stickers vividly representing each person who has previously died from complications. He is effectively complaining that GiveWell refrains from engaging in moral misdirection. It’s extraordinary, and really brings out why this concept matters.

Honest public communication requires taking care not to mislead general audiences.

Wenar claims to be promoting “honesty”, but the reality is the opposite. My understanding of honesty is that we aim to increase importance-weighted accuracy in our audiences. It’s not honest to selectively share stories of immigrant crime, or rare vaccine complications, or that one time bandits killed two people while trying to steal money from an effective charity. It’s distorting. There are ways to carefully contextualize these costs so that they can be discussed honestly without giving a misleading impression. But to demand, as Wenar does, that costs must always be highlighted to casual readers is not honest. It’s outright deceptive.

Further reading

There’s a lot more to say about the bad reasoning in Wenar’s article (and related complaints from other anti-EAs). One thing that I especially hope to explore in a future post is how deeply confused many people (evidently including Wenar) are about the role of quantitative tools (like “expected value” calculations) in practical reasoning about how to do the most good. But that will have to wait for another day. [Update: now here.]

In the meantime, I recommend also checking out the following two responses:

Richard Pettigrew: Leif Wenar's criticisms of effective altruism

Bentham’s Bulldog: On Leif Wenar’s absurdly unconvincing critique of effective altruism

Compare all the progressive hand-wringing over wildly speculative potential for causing “harm” whenever politically-incorrect views are expressed in obscure academic journals. Many of the same people seem completely unconcerned about the far more obvious risks of spreading anti-philanthropic misinformation. The inconsistency is glaring.

My best guess at what is typically going on: I suspect many people find EAs annoying. So they naturally feel some motivation to undermine the movement, if the opportunity arises. And plenty of opportunities inevitably do arise. (When a movement involves large numbers of people, many of whom are unusually ambitious and non-conformist, some will inevitably mess up. Some will even be outright crooks.) But once again, even if some particular complaints are true, that’s no excuse for predictably leading their audiences to believe much more important falsehoods.

One difference: Don’s behavior is naturally understood as stemming from hateful xenophobic attitudes. I doubt that most critics of EA are so malicious. But I do think they’re morally negligent (and very likely driven by motivated reasoning, given the obvious threat that EA ideas pose to either your wallet or your moral self-image). And the stakes, if anything, are even higher.

In the same way, I wish anyone invoking dismissive rhetoric about utilitarian “number-crunching” would understand that those numbers represent people’s lives, and it is worth thinking about how we can help more rather than fewer people. It would be nice to have a catchy label for the failure to see through to the content of what’s represented in these sorts of cases. “Representational myopia,” perhaps? It’s such a common intellectual-cum-moral failure.

Though he doesn’t even mention GiveDirectly, a long-time EA favorite that’s often treated as the most reliably-good “baseline” for comparison with other promising interventions.

As Bentham’s Bulldog aptly notes:

Perhaps Wenar should have applied the “dearest test” before writing the article. He should have looked in the eyes of his loved ones, the potential extra people who might die as a result of people opposing giving aid to effective charities, and saying “I believe in my decisions, enough that I’d still make them even if one of the people who could be hurt was you.”

As Scott Alexander (of Astral Codex Ten) puts it:

I want to make it clear that I think people like this Wired writer are destroying the world. Wind farms could stop global warming - BUT WHAT IF A BIRD FLIES INTO THE WINDMILL, DID YOU EVER THINK OF THAT? Thousands of people are homeless and high housing costs have impoverished a generation - BUT WHAT IF BUILDING A HOUSE RUINS SOMEONE'S VIEW? Medical studies create new cures for deadly illnesses - BUT WHAT IF SOMEONE CONSENTS TO A STUDY AND LATER REGRETS IT? Our infrastructure is crumbling, BUT MAYBE WE SHOULD REQUIRE $50 MILLION WORTH OF ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW FOR A BIKE LANE, IN CASE IT HURTS SOMEONE SOMEHOW.

“Malaria nets save hundreds of thousands of lives, BUT WHAT IF SOMEONE USES THEM TO CATCH FISH AND THE FISH DIE?” is a member in good standing of this class. I think the people who do this are the worst kind of person, the people who have ruined the promise of progress and health and security for everybody, and instead of feting them in every newspaper and magazine, we should make it clear that we hate them and hold every single life unsaved, every single renewable power plant unbuilt, every single person relegated to generational poverty, against their karmic balance.

They never care when a normal bad thing is going on. If they cared about fish, they might, for example, support one of the many EA charities aimed at helping fish survive the many bad things that are happening to fish all over the world. They will never do this. What they care about is that someone is trying to accomplish something, and fish can be used as an excuse to criticize them. Nothing matters in itself, everything only matters as a way to extract tribute from people who are trying to do stuff. “Nice cause you have there . . . shame if someone accused it of doing harm.”

Note that GiveWell is very transparent in their full reports: that’s where Wenar got many of his examples from. But to list “deaths caused” on the front page would mislead casual readers into thinking that these deaths were directly caused by the interventions. Wenar instead references very indirectly caused deaths—like when bandits killed two people while trying to steal money from an effective charity, or when a charity employs a worker who was previously doing other good work. Even deontologists should not believe in constraints against unintended indirect harm of this sort—that would immediately entail total paralysis. Morally speaking, every sane view should agree that these harms merely count by reducing the net benefit. They aren’t something to be highlighted in their own right.

I appreciate the desire to be charitable and only focus on the literal truth or falsity of the criticism (or what it omits) but I fear that in explaining what's going on with this reaction to EA's I think it's necessary to look at the social motivations for why people like to rag on EA.

And, at it's core, I think it's two-fold.

First, people can't help but feel a bit guilty in reaction to EAs. Even if EAs never call anyone out, if you've been donating to the make a wish foundation it's hard not to hear the EA pitch and not start to feel guilty rather than good about your donation. Why didn't you donate to people who needed it much more.

A natural human tendency in response to this is to lash out at the people who made you feel bad. I don't have a good solution to this issue but it's worth keeping in mind.

Secondly, EA challenges a certain way of approaching the world that echoes the tension between STEM folks and humanities individuals (and the analytic continental divide as well).

EA encourages a very quantative, literal truth oriented way of looking at the world. Instead of looking at the social meaning of your donations, what they say about your values and how that comments on society, it asks us to count up the effects. At an aesthetic level this is something that many people find unpleasant and antithetical to how they approach the world. In other words, it's the framework that is what really does most of the offense not the actual outcomes. You could imagine pitching those same things in a different way where it wasn't about biting hard bullets but all stated in terms of increasing the status of things they approved of and I think the reaction would be different.

I also see that if someone strongly commits themselves to socialism such that they make it their identity, then they, even if they are vegan, attack effective altruists for "not taking the systemic issues of capitalism" seriously. If they just made "doing good" or "making the world a better place" their identity and searched for whatever system achieves that goal, then they would not attack effective altruism. And, well, they would not attack real capitalism either because real capitalism does maximize wellbeing more compared to real socialism.