A major motivation for utilitarianism is that it, more than any other view, really takes seriously the moral datum that everyone matters equally. Other common views are often problematically nationalist, speciesist, and near-termist. Prioritarian views explicitly give less weight to the better-off, and egalitarianism goes even further as it valorizes harms to the best off as in some ways good (increasing equality), even when this is in no way good for anyone. Deontic constraints, relying as they do on a doing-allowing distinction, favour those in a more privileged default position (e.g. the person on the footbridge over the five on the trolley tracks), even though all involved would’ve agreed from behind a veil of ignorance that the greater number should be saved. That all seems indefensible to me.

Despite all this, many remain deeply skeptical of the claim that “equal mattering” supports utilitarianism—but often, I think, for deeply confused reasons. In this post, I’ll set out some important correctives to common assumptions about this topic. (The vast majority of people are deeply confused about this topic, so it could really help improve our collective moral understanding if you’re inspired to share this post widely.)

Five Theses on Mattering:

Valuing People Equally ≠ Valuing Equality

We Value People Equally by giving Equal Consideration to their Interests

Mattering Equally ≠ Identical Treatment or Equal Outcomes

How Much One Matters ≠ the Value of One’s Prospects

Denying Instrumental Value ⇒ Denying Equal Mattering

1. Valuing People Equally ≠ Valuing Equality

Utilitarianism is importantly distinct from egalitarianism. I think that’s a good thing. We should value concrete individuals, not abstract, relational features of distributions such as equality. The Leveling-Down Objection to egalitarianism gets its force from highlighting (i) how these could come into conflict, and (ii) how it seems perverse to value equality per se in the face of such conflict. So, valuing equality per se is something other than (and, in my view, less appealing than) valuing individuals equally. (Of course, utilitarians may still support income redistribution insofar as the benefits to the poor of being able to meet their basic needs vastly outweigh the costs to the rich of having to pay higher taxes — and so long as the higher taxes don’t have unintended consequences so detrimental as to outweigh these benefits.)

2. We Value People Equally by giving Equal Consideration to their Interests

A very common mistake is to claim that utilitarians really value utility rather than individuals.

It’s possible to imagine a view that takes this form — in my published work, I call it Utility Fundamentalism. But it’s an awful straw man to just assume that another’s utilitarianism takes this unpalatable form, when a much better alternative—Welfarism—is available. According to welfarist utilitarians, “utility” only matters because it is good for individual welfare subjects. Most fundamentally, individuals matter, and I want to promote happiness and other welfare goods because and insofar as that will make life better for people (and other sentient beings). That’s my view.

For those who are interested, my linked paper also refutes more sophisticated versions of the ‘value receptacle’ objection, including the worry that (some forms of) utilitarianism treat individuals as fungible means to the aggregate welfare. Again, I show that this gets the order of explanation reversed, and that there is no barrier to adopting a more charitable interpretation of utilitarianism that gives normative primacy to separate individuals (whilst still allowing tradeoffs to be made between their conflicting interests).

3. Mattering Equally ≠ Identical Treatment or Equal Outcomes

People sometimes assume that equal-mattering entails identical treatment. But of course this only follows if all else is equal. As Dworkin famously wrote, “If I have two children, and one is dying from a disease that is making the other uncomfortable, I do not show equal concern if I flip a coin to decide which should have the remaining dose of a drug.” If you treat low stakes for one as equal in importance to objectively higher stakes for another, you are evincing disrespect for the latter person—egregiously so, if the difference in magnitude is sufficiently great.

(Similar remarks apply if we imagine that some additional minor cost must be imposed on the first child in order to make the medicine work on the second. Obviously, you could love both kids equally, and give equal weight to their interests, while imposing a small cost to one in order to avert far greater costs to the other.)

So we can see that benefiting some at the expense of others is in fact clearly compatible with (and sometimes even required by) valuing all equally. It just requires that the benefits in question clearly outweigh the costs, and we count each benefit and cost according to its true weight—no matter who it is that receives the cost or benefit in question. Crucially, we would still endorse the tradeoff even if the identities were shuffled or reversed. And everyone involved would agree that it’s a prudent tradeoff from behind a veil of ignorance. That’s how you can tell that it’s impartially justified, counting all equally, and not some kind of dastardly bias or favoritism.

As further explained on utilitarianism.net:

Utilitarianism counts the well-being of everyone fully and equally, neglecting none… That is precisely why the theory directs us to do whatever will best help all those individuals. This may lead to outcomes where some particular individuals are disadvantaged, but it is important not to conflate ending up worse-off with counting for less in the process of determining what would be best overall (counting everyone’s interests equally).

Again: it’s no indication of bias to prefer a greater benefit to one over a lesser benefit to another. That’s just what follows from giving equal weight or consideration to the interests of both individuals. Remember this principle, as it is vital to what follows.

4. How Much One Matters ≠ the Value of One’s Prospects

People mostly grasp the previous point when comparing ordinary costs and benefits to one’s quality of life. But this understanding goes out the window when comparing saving lives with very different future prospects.

The basic problem here is that people conflate the value of one’s future prospects—that is, how strongly a benevolent bystander would wish for you to survive the present moment—with how much one matters as a moral being. But these are completely different concepts!

To demonstrate this, imagine a medic comes across a saint and an ordinary sinner bleeding out on a battlefield, with time enough to save only one of them. And suppose the medic is not a utilitarian, but a desert-adjusted welfarist. Suppose they give twice as much weight to the interests of the saint. That is, they regard the saint as mattering twice as much as the sinner. If they could give a moderate benefit to the sinner, or a lesser (51+%) sized benefit to the saint, they’d opt for the latter. But suppose the saint is much more badly injured, and could not be restored to full health. Indeed, if the medic saved the saint, despite their best efforts, the saint would live bedridden and in agony for the rest of her days. It would not be a positive future. The sinner, by contrast, could easily be saved and restored to full health. So the medic saves the sinner over the saint. Does it follow that the medic regards the sinner as “mattering more”? NO. Like we’ve said, they would much prefer to give a benefit of this size—restoring full health and happiness—to the saint. But they can’t.

Now tweak the case so that the saint’s future would not be filled with agony. It wouldn’t be negative. But still, it would only be at a tiny fraction of the quality of life available to the sinner. So again, the medic saves the sinner—while, again, wishing they could do even half so much good for the saint that they care much more about. Does it follow now that the medic counts the saint for less? Again, NO. The medic counts the saint for more, but still regards a vastly (more than double as good) future for another as taking moral priority over a meagre benefit to the saint.

So, preferring a life with a better future over another with a less-good future plainly does not entail counting those who miss out for less. It’s even compatible with counting those who miss out for more (though of course a utilitarian wouldn’t do that). So this objection to utilitarianism rests on a straightforward conceptual mistake.

Utilitarians value all sentient beings equally in the sense that they would feel equally positively about giving a particular-sized welfare benefit to any of those beings (all else equal). But, crucially, how worthwhile it is to “save someone’s life” depends on the value of their future prospects, not (just) on how much they matter as a moral being. And we don’t value all future prospects equally—that would be daft.

You should prefer for someone to have 50 more years of happy and richly human life than for that same person to just have 50 days of crude chicken-experience before they die. So if you can either save a chicken for 50 days or a person for 50 years, caring equally about each individual commits you to saving the latter. They have more at stake; it’s a greater benefit for them. That’s not to say that they matter more (as though you’d sooner give 50 chicken-quality days to that human than 50 human-quality years to the chicken); but just that the future prospect you can offer them is greater than what you can offer the chicken. To do anything else would be to deny full weight to the greater interest, disrespecting the individual who truly had more at stake.

And so it goes in any other case where people differ in their life prospects. The critics who claim that utilitarian verdicts are “discriminatory” are—as the above argument shows—quite simply conceptually confused. You can either respect that everyone matters equally or you can pretend that all future prospects are equally valuable and so disrespect those who truly have more at stake. Utilitarians opt for the former. Their critics prefer the latter, which is easier to (mis)represent as the “moral high ground” to those who don’t understand the distinctions drawn in this post. It’s a deeply perverse situation.

[For more detailed discussion of these issues, see my 2016 paper, ‘Against “Saving Lives”: Equal Concern and Differential Impact’.]

5. Denying Instrumental Value ⇒ Denying Equal Mattering

So far, we’ve just been talking about the direct value of benefiting someone, for their own sake. But consequentialism also directs us to take indirect benefits into account, e.g. if by helping someone I would thereby also cause several others to be helped. Some find this objectionable:

Frances Kamm, for example, claims:

[T]o favor the person who can produce [extra utility] is to treat people “merely as means” since it decides against the person who cannot produce the extra utility on the grounds that he is not a means. It does not give people equal status as “ends in themselves” and, therefore, treats them unfairly.

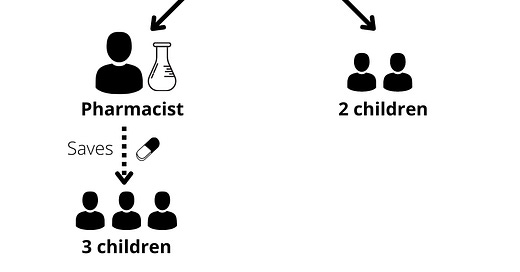

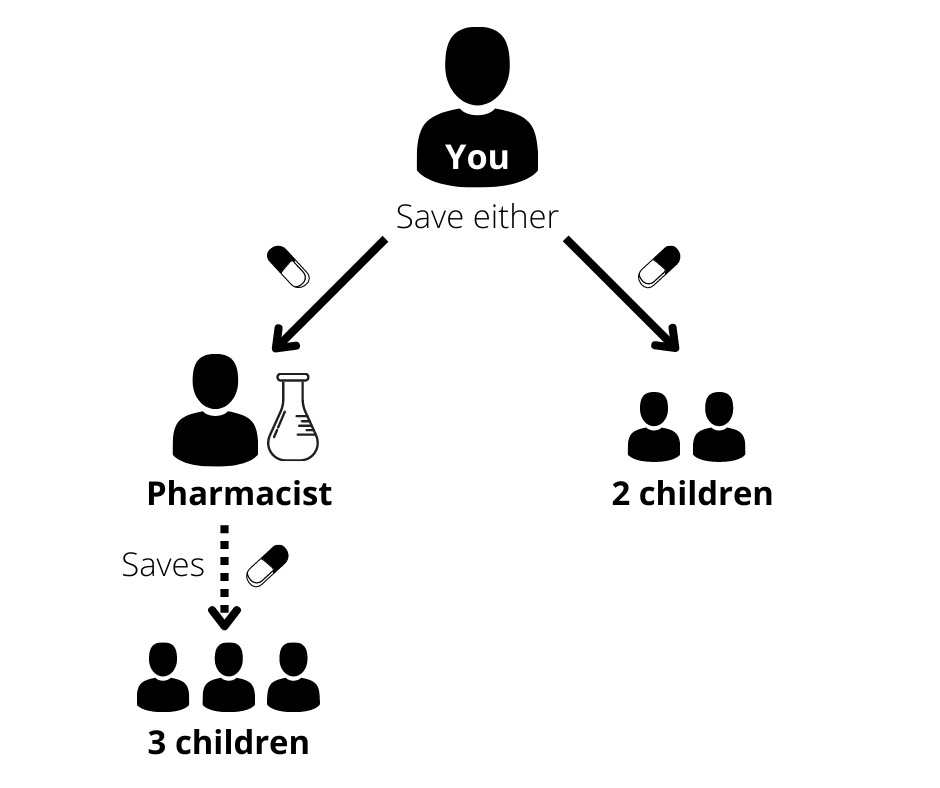

This is, again, quite simply conceptually confused. Consider the Pharmacist case from utilitarianism.net:

Suppose that you are faced with a medical emergency, but only have enough medicine to save either one adult or two children. Two children and an adult pharmacist are on the brink of death, and three other children are severely ill, and would die before anyone else is able to come to their assistance. If you save the pharmacist, she will be able to manufacture more medicine in time to save the remaining three severely ill children (though not in time to save the two that are already on the brink). If you save the two children, all the others will die. What should you do?

Kamm says you should save the 2 children, rather than saving the pharmacist and thereby also 3 children. I say that this verdict reflects an obscene failure to give due weight to the interests of the 3 children:

[T]he utilitarian does not ascribe any extra intrinsic value to the pharmacist. The pharmacist is thus not regarded as any more important as an end in herself. Intrinsically, or in herself, she may be regarded equally to any other individual. We prioritize saving her over the two children simply because we can thereby save the three other children in addition. The utilitarian's disagreement with Kamm stems not from the utilitarian unfairly giving extra weight to the pharmacist, but from Kamm's failure to give equal weight to the three children who we could save by means of saving the pharmacist.

As this case shows, if you fail to take instrumental value into account, then you implicitly deny that those you could benefit indirectly (e.g. the three children) matter as much as those you can benefit directly. So this is yet another example of non-utilitarians failing to accord equal weight to all, while falsely projecting this failure on to those who are actually counting all equally.

Coda: Good Rules May Point Away from Principle

It’s important to stress that this post is all about matters of principle. We should all agree that the above five theses are true in principle. But it doesn’t follow that we should always try to follow these principles in practice. As I explain here:

[T]here are many cases in which instrumental favoritism would seem less appropriate. We do not want emergency room doctors to pass judgment on the social value of their patients before deciding who to save, for example. And there are good utilitarian reasons for this: such judgments are apt to be unreliable, distorted by all sorts of biases regarding privilege and social status, and institutionalizing them could send a harmful stigmatizing message that undermines social solidarity. Realistically, it seems unlikely that the minor instrumental benefits to be gained from such a policy would outweigh these significant harms. So utilitarians may endorse standard rules of medical ethics that disallow medical providers from considering social value in triage or when making medical allocation decisions. But this practical point is very different from claiming that, as a matter of principle, utilitarianism’s instrumental favoritism treats others as mere means. There seems no good basis for that stronger claim.

I suspect that the most strident and panicky opposition to utilitarianism stems from a failure to distinguish what’s true in principle from what’s apt to guide us in practice. Crude attempts to “implement” utilitarianism in stupid and short-sighted ways could indeed be very scary! But it’s important to note that the more feverish fears (e.g. of “forced birth” policies) are also really clearly unwarranted on utilitarian grounds. Defenders of the theory have plenty to say about how to implement it more wisely. But that’s a topic for another day.